Netherlands is the land of two fast phenomenon, the wind and cycling. I take my bike for almost every errand due to the superior biking infrastructure. When I ride my bike, there’s almost always the sound of wind filling my ears. It’s not just background noise, it’s often loud enough to drown out almost everything else. Lately I play around with the wind by changing the angle of my head to 90 degrees, I can make it completely disappear. If I turn my head slightly left or right, the noise drops off slowly. That change caught my attention. I started wondering what exactly I was hearing, and why a small movement of my head could make such a big difference. It didn’t feel like just air moving, it felt like pressure, turbulence, and sound all mixed together. Here is an attempt at trying to explain the phenomenon. Later, I will try to explore if this is loud enough to effect the hearing and in places like in the Netherlands, whether we need some hearing protection together with the bikes when biking in the wind.

Cutting Through Air#

When you’re biking, you’re literally pushing through still air. The air has to move around your head, face, and ears. That flow doesn’t stay smooth; it breaks apart and becomes turbulent. Behind your head and around your ears, small swirls and eddies form and collapse constantly. Each one of those pressure changes hits your eardrum and adds up to what we hear as the roar of wind. The faster you go, the stronger that turbulence becomes. What you’re hearing is essentially the air’s reaction to your movement through it. In fluid dynamics, this falls under aeroacoustics Aeroacoustics , the study of how moving air generates sound when it flows around solid objects like our heads.

A 2025 study by Riedel, C., et al. (2025) used computational fluid dynamics to simulate airflow around human ears. They showed that small changes in angle or ear shape can change the turbulence pattern and how much sound pressure reaches the ear. On a bike, that explains why tilting or turning your head changes what you hear so dramatically. The airflow shifts, turbulence forms differently, and one ear might suddenly find itself in a quieter zone.

The phenomenon is as follows, When you turn your head, the airflow around it changes. The ear that faces away from the wind moves into a calmer zone behind your head where the air isn’t as chaotic. The pressure fluctuations drop off, and that ear suddenly hears almost nothing. The other ear, now facing into the wind, gets the full turbulence. That’s why a small rotation can make the wind sound shift from both ears to just one side or even go nearly silent.

Measured Noise Levels and Hearing Risk#

A 2017 study by Seidman, M. D., et al. (2017) measured wind-generated noise in a controlled setting for cyclists. They found levels starting around 85 dB at 10 mph and increasing up to about 120 dB at 60 mph. The highest readings came from the downwind ear when it was turned 90 degrees away from the airflow. They recommend hearing protection.

To put that in context:

- 85 dB is the level where hearing damage can start with long exposure.

- Around 100 dB, damage can occur in minutes.

- 120 dB is close to the pain threshold.

That means even moderate cycling speeds, combined with strong headwinds like those common in the Netherlands can reach levels that risk hearing injury over time.

Estimating the Sound Based on Wind Speed#

The Seidman et al. results give us two key points:

- 84.9 dB at 10 mph

- 120.3 dB at 60 mph

That’s roughly a linear increase of 0.708 dB per mph, with an intercept near 77.8 dB.

So we can approximate:

SPL (dB) ≈ 77.8 + 0.708 × V_rel(mph)

where V_rel is your relative air speed (bike speed plus or minus wind, depending on direction).

Relative airspeed formula#

If the wind makes an angle θ with your direction of travel:

V_rel = √(V_bike² + V_wind² − 2·V_bike·V_wind·cosθ)

where θ = 180° for a headwind, 0° for a tailwind, and 90° for a crosswind.

For example, at 25 km/h on a calm day, that’s about 15.5 mph, giving ≈ 88.8 dB. With a 40 km/h headwind, the relative speed is roughly 65 km/h (40 mph), which estimates near 106–108 dB — high enough to risk damage with long exposure.

Estimated wind noise levels while cycling#

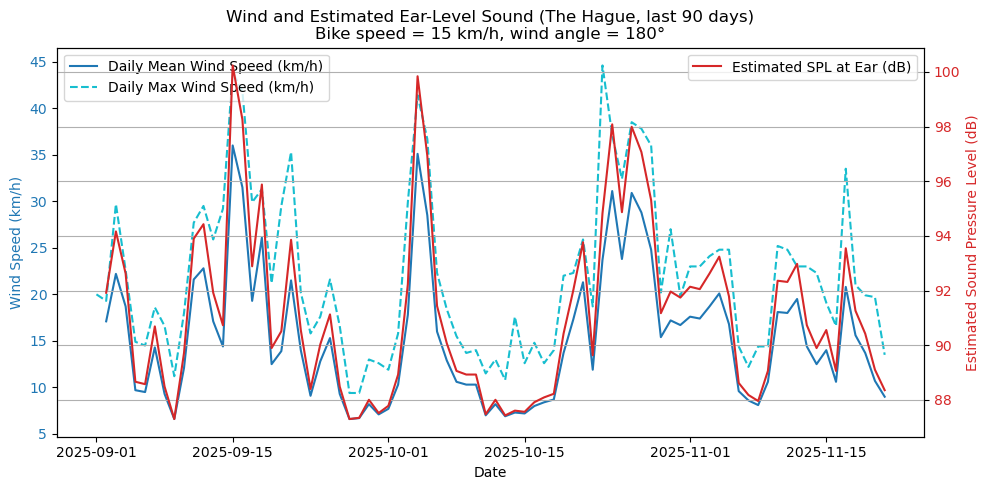

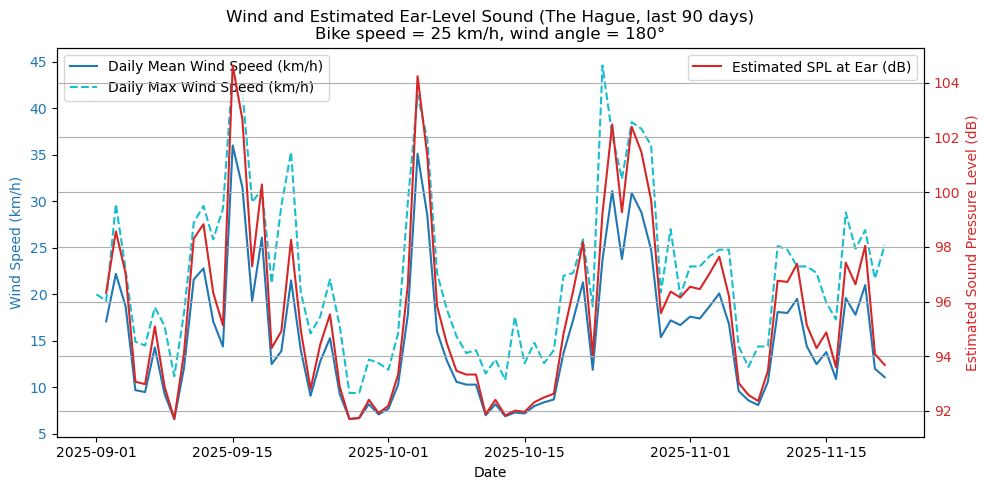

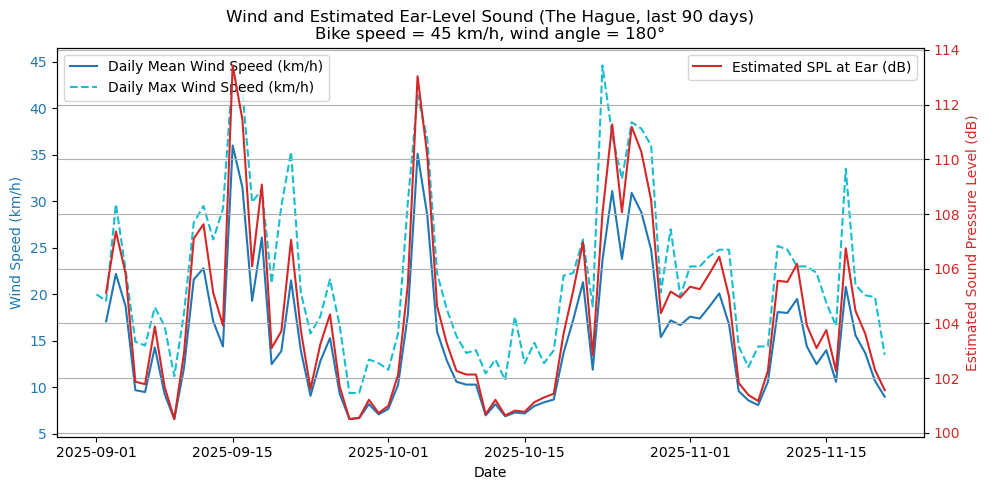

You can combine this with real wind data to visualize it. I pulled the recent wind speeds in The Hague for the last 90 days and estimated the corresponding sound level at your ear for a given cycling speed and wind direction.

This plot shows the relationship between cycling speed and the estimated sound pressure level (SPL) at the rider’s ear for a moderate pace of around 15 km/h. It visualizes how even gentle riding can generate noticeable wind noise once the air starts flowing around the ears.

At 25 km/h, the relative airspeed and resulting turbulence around the head increase sharply, pushing the noise levels toward ranges where long exposure might start to matter for hearing comfort or protection.

bike_speed: your average riding speed (km/h)wind angle: wind direction relative to your travel (180 = headwind)

The result shows how even typical Dutch conditions can push wind noise near or over 90 dB, enough to matter if you’re riding daily for very long periods of time.

| Sound Level (dB SPL) | Safe Exposure Time (approx.) |

|---|---|

| 60 dB | Indefinite |

| 70 dB | Indefinite |

| 85 dB | 8 hours |

| 90 dB | 2 hours |

| 95 dB | 1 hour |

| 100 dB | 15 minutes |

| 110 dB | <1 minute |

| 120 dB | Instant pain and possible damage |

| 130 dB+ | Instant, permanent damage |

The customary section about Fat bike hate#

In the Netherlands, many modified fatbikes easily exceed the legal 25 km/h limit, sometimes reaching 40–50 km/h on bike paths. Riders caught with tuned motors can face fines of around €325, and those speeds not only break the law but also put both the rider and others at serious risk. At 45 km/h, the estimated wind noise at the ears already approaches levels associated with potential hearing damage, a small reminder that the danger isn’t just legal or physical, but acoustic too.

Hearing Protection#

Given those noise levels, it’s reasonable to think about hearing protection for cycling. There are earplugs and covers designed for riders that cut down the wind noise but still let you hear ambient sounds like traffic. On long or windy rides, using something like that might help prevent both fatigue and hearing damage. I prefer wearing a Beanie/Muts and it helps a lot. Thankfully most cycle trips in the Netherlands are urban and usually short distances. Also the few times I ventured cycling in the rural parts during storms in Haarlemmermeer, I did not see any other person and also the head wind is so strong that it takes a lot of energy to cycle even short distances.